|

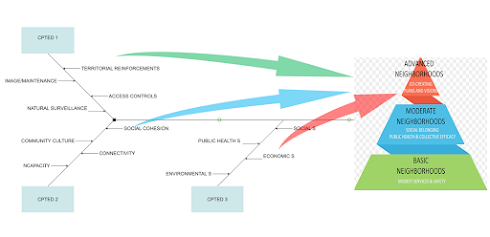

| Walkable, carless, pro-social, and safe. What do future neighborhoods look like? |

by Gregory Saville

With apologies to Mark Twain, that quote above is what came to mind as 2021 ends. Such a turbulent year with so many distractions – Covid, mass shootings, increasing crime, social unrest! It’s hard to look back through the lens of the 24-hour news cycle and social media and not conclude that we are going to hell in a handbasket.

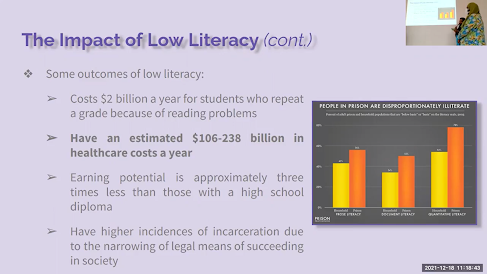

Do yourself a solid and have a read of Bailey and Tupy’s exceptional book Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know. They use those increasingly rare things called facts to soundly debunk the doom-and-gloom-is-everywhere theory.

|

| Bailey and Tupey's book Ten Global Trends - using research and facts to tell the truth. |

When you've read Global Trends, (and after you mask up, vaccinate, and elect better politicians with better policies), then give a thought to doing the right thing for safety in 2022 and learn some state-of-the-art theories in neighborhood crime prevention. There are a few good ones to pick from, but be careful - some only go halfway.

Here are a few to watch:

SITUATIONAL PREVENTION

In the 1970s they created electric car alarms to cut auto theft. You know, those pulsing lights and blaring horn alarms (BLEEP...BLEEP...BLEEP) that, nowadays, most people just ignore.

Around the 1980s, they created The Club to lock a steering wheel so thieves could not drive the car. Unfortunately, thieves adapted and learned to hacksaw the steering wheel and slide The Club off. One thief said: “So if it takes 60 seconds to steal a car, it now takes 90.”

|

| The Club auto theft prevention device - photo Wiki Creative Commons |

In the 1990s auto manufacturers adopted another situational crime prevention approach to harden the target. They created vehicle immobilizers, electronic devices that prevent a car engine from starting until a proper key transponder is present. Immobilizers prevent hot wiring and also eliminate that annoying BLEEP...BLEEP...BLEEP.

What is the result of situational crime prevention?

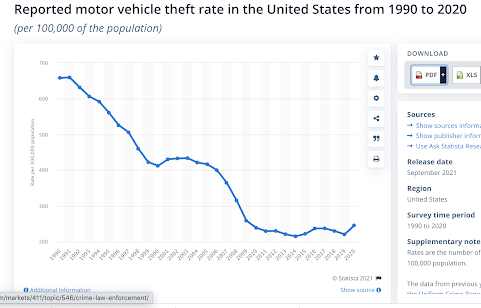

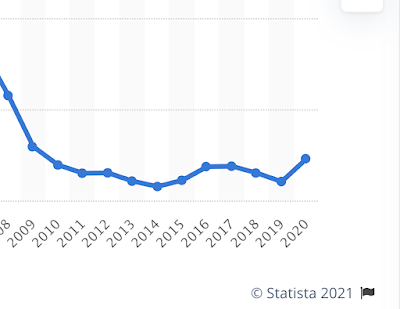

Some criminologists say the increasing adoption of security technologies has cut crime opportunities all over the world. Crime everywhere has decreased and auto theft has plummeted, as you can see on the graph.

|

| Auto theft rates sunk as theft devices were adopted... |

Except, there are a few glaring problems with this theory. First, not all crime rates around the world have declined in spite of more security technology! (Latin America comes to mind).

Second, consider this...

|

| ...up until the past decade when rates began increasing. |

Even with improvements to auto theft prevention, decade after decade, in the past ten years auto theft rates have NOT declined. In fact, they have started to increase! Look at the reality in the chart above of the past 10 years! How can this be? Security technologies have not vanished.

Why are auto theft rates increasing? Perhaps the situational prevention theory spends so much time hacking at the branches of crime opportunity, it missed digging at the roots of crime causation?

FOCUSED DETERRENCE

Consider another recent prevention theory - focused deterrence, also known as CVI (community violence interrupters). I blogged on this promising strategy a few weeks ago.

In a 2019 article, "There is no such thing as a dangerous neighborhood", Stephen Lurie says we should not fix broken neighborhoods but rather target the small group of chronic offenders in those neighborhoods who cause most problems. That is how CVI intervenes in the cycle of violence. Says Lurie:

"The notion that public disorder drives criminality can seem an intuitive approach to public safety. But if people understand that most serious violence circles specific interpersonal group dynamics in structurally disadvantaged communities, order maintenance policing seems more like what study after study shows it is: an unnecessary evil."

Regrettably, permanently resolving a complex crime problem is not as simple as intervening with the offender before they rob or shoot. As the late Desmond Tutu warned, "There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they're falling in."

No doubt we need to do something fast when violence threatens and that is something at which situational prevention and focused deterrence both excel. But there is no hiding the fact that they both hack at the branches - neither one alters structurally disadvantaged communities in any meaningful way.

Criminologists will tell you there are many seeds to crime causation. But over a half-century of criminological research amply demonstrates that the dysfunction, trauma, substance abuse, and blight in disadvantaged communities provide the breeding ground from where most chronic offenders emerge in the first place. Severely disadvantaged places create an endless supply of chronic offenders and if we want to dig at the roots of crime, and not hack at the branches, we must face those structural disadvantages. That is from where hope emerges and that is how we do the right thing.

ANOTHER WAY - SAFEGROWTH

Some criminologists and law enforcement officials will complain that it is exceedingly difficult, (and takes a long time) to deal with deep structural problems in neighborhoods. Part of that is because the expertise and professions that deal with such problems are not found within criminology or law enforcement. They are found in economic development, urban planning, neuropsychology, cognitive science, and education.

That is why SafeGrowth practitioners collaborate with experts in all those different fields and then work with residents to co-develop prevention plans. This kind of deep-dive capacity-building is neither simple nor fast. Ultimately, SafeGrowth marries community development and social prevention with 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Generation CPTED. The method has been successful for decades. Our SafeGrowth book describes how we keep our eyes on the real prize.

A few other recent examples:

- Last week’s blog by Mateja on the Philadelphia Livability Academy shows how to create community leaders and launch projects.

- Tarah’s blog on how we create Third Place hubs shows how urban design works.

- Tod Schneider's blog on Community Supported Shelters provides a way to turn homelessness into something humane.

These are only a few of many ways forward. In 2022 let’s do the right thing and not lose sight of the fact that, if we want to build a better society, we actually have to build a better neighborhood.

Happy New Year.