|

| Preventing crime has much more to it than cameras |

by Gregory Saville

Recently, I was asked whether we know enough about crime to prevent it. Simple enough, you would think. Isn't the study of crime "scientific" and, if so, doesn't that provide a simple answer? Turns out, it isn’t that simple.

Criminologists are concerned directly with the well-being of everyday people and their families, their property, and their safety. Scientists, of course, are as well – especially medical researchers searching for cures to diseases or meteorologists who want to warn you to stay away from bad weather.

Yet scientists often study elemental phenomena with seemingly little direct impact on daily life. That is not always true, but the gulf from science theory to practical application can be wide. In criminology, it can be a very narrow gulf from theory-to-effect. Criminology speaks to the lives of everyday people (at least some criminology). In pure science, there are many branches where that is not so, particularly in theoretical research.

Consider titles of scientific studies: Non-Reciprocal Coupling in Photonics, Lightwave-driven electrons in a Floquet topological insulator, or Verification of Toronto temperature and precipitation forecasts for the period 1960-1979.

[Disclosure: On that last study my name appears as one of eight co-authors. It was my first scientific publication as a young climatology student. I got my academic start in the physical sciences, hence my obsession with the science in social science.]

|

| Using the scientific method comes with some basics - hypothesis-testing is one |

THEORY BASICS

The reason for this gulf is simple – pure sciences start with theoretical basics. What is atomic structure? What is the life cycle of living organisms? Long before science gets to apply anything to the real world, basic theoretical questions must be answered. Laws of nature are identified.

In criminology, that step has been difficult. Consider the most fundamental theoretical question in criminology: What causes crime? That question still remains elusive. There are disagreements about whether the cause of crime is biological, sociological, cultural, economic, psychological, political, or some weird recipe of all of them.

Imagine an aeronautical engineer without a basic law of flight and aerodynamics? There would be no jets! Imagine a medical doctor without a basic law of biochemistry and anatomy. There would be no medicine.

How can criminology proceed without such basic laws or answers to theoretical questions?

|

| What causes crime? Even this simple question does not have a simple answer |

PROCEEDING WITHOUT BASICS

Sometimes criminologists adopt a theoretical position and then test that against research data. Theory testing is a long-proven method of science and there are criminologists who call themselves “crime scientists” who advocate for this. Crime science is a kind of overlap between environmental criminology and experimental criminology.

Crime science aims directly at the crime event itself and those who commit it with the intent of preventing it. It claims the scientific method at its core.

These are all laudable goals. So if science is at the core, then the scientific method demands theory-testing. That means the very first step in theory-testing is clearly stating a hypothesis, something quite rare in criminological studies.

|

| The methods of science have some basic steps to follow Image courtesy of Brian Brondel at English Wikibooks, CC BY-SA 2.5 |

Unfortunately, when I read a few recent issues of the journal Crime Science, I could not find a single clearly stated hypothesis. Hardly a recipe for science! Science always attempts to measure things, and that usually means statistics and formulas. However, none of that matters if the hypothesis is not based on a logical chain of linked concepts (or not stated at all).

Am I nitpicking by seeking hypotheses with a clearly stated formula? After all, many authors simply write out their hypotheses in more descriptive text, something I’ve done many times. But keep in mind that if scientific veracity is the goal, then stating a clear hypothesis is not a minor quibble.

None of this is meant to take anything away from Crime Science. Read the journal. It has some fascinating studies such as the relationship between lush tree canopies on city streets and nearby crime rates (one of the same predictions we make in our Third Generation CPTED theory).

|

| Biologists classify tree types before posing hypotheses - a classification method that creates typologies |

TYPOLOGIES – CLASSIFY THE DAMN THING

Typologies are the things that basic sciences employ during the founding of any field. Typologies are those things like Darwin’s famous charts of finches in the Galapagos Islands as the foundation of evolution (or tree typologies by botanist Patrick Matthew long before Darwin).

Typologies are the first step to mapping out the different categories of a phenomenon such as crime and that is how you begin to understand it. They are things on which hypotheses are constructed. One building block provides the foundation for the next and eventually, a theory emerges that is tested in experiments.

Criminology has very few typologies. Some criminologists may take exception to that statement. However, when challenged to produce some, they seldom produce more than whether criminals are abnormal versus normal, expressive versus instrumental or professional, petty, or white collar.

Sometimes criminologists provide their own typologies within their own studies. That’s the beginning. But there is a big difference between typologies shared by an entire field and one made up on the spot. There really are very few overarching, agreed-upon classification typologies within the criminological enterprise. One exception might be the maturation effect (the stoppage of crime as offenders of specific genders age). But that too has fallen from grace in criminological theory.

|

| Doing science is more than stating hypotheses or conducting random tests |

DOING SCIENCE?

Some publications make a valiant effort to classify the phenomena of different crimes. A good example is Martin Andresen’s books on environmental criminology. If you have not read Martin’s latest version of environmental criminology, do yourself a favor. Read it!

Another great effort to create crime typologies is the book I reviewed by crime analyst Deborah Osborne: Elements of Crime Patterns.

Osborne's book is possibly the first thorough attempt to create a typology of different crime types, modalities, tools, and signature behaviors. Her book was published last year, over a century after the criminological enterprise began, suggesting that existing crime theories are akin to the cart before the horse.

THE EVIDENCE-BASED (EB) CROWD

Now there is a new crowd on the criminology block – the evidence-based coalition. This is the latest version of the search for crime patterns using science that has always been embedded within criminology. For example, Robert Merton the famous criminologist (and former street gang member), called for scientific thinking in his writing almost a century ago (earlier European criminologists did the same).

There is now a federal website dedicated to evaluating crime policies with EB methods. The premise is that programs will improve only through the gold standard of scientific testing called the randomized controlled trial (a standard that some criminologists like Malcolm Sparrow consider impractical). So while evidence-based methods wear the crown of the scientific method, they do that to test programs and evaluate strategies. That may not have anything to do with criminological theory. Testing programs is not the same as testing scientific theories.

Remember the definition of the scientific method:

“the scientific method is critical to the development of scientific theories, which explain empirical laws in a scientifically rational manner… it is the technique used in the construction and testing of a scientific hypothesis.”

|

| "Doing science" in crime prevention means working with the community, using science, and collaborating with others |

WHERE DOES THAT LEAVE US?

Do all these claims of scientific respectability in criminology mean we truly know enough about crime to prevent it? Are all these efforts enough?

On one hand, they are probably not enough, but they are a work in progress. On the other hand, they show an emerging field with committed researchers who dedicate themselves to improving this thing we call criminology. I have no idea whether the current state of criminology can be properly termed a “science”, but I applaud the effort to reach that goal.

What about the prevention of crime? We have known since the ancient Egyptians that ingredients in some tree saps can alleviate pain. When German chemists figured out how to manufacture that into aspirin, it became the pain reliever we know today. Science perfected those ingredients and we learned that too much aspirin can cause stomach ulcers, but the right amount is one of the best pain relievers in history.

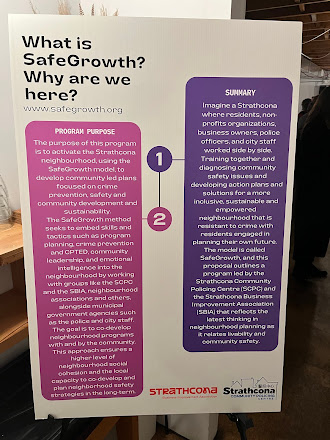

We can prevent many types of crime and improve livability. We know that from our experience and research in SafeGrowth. There is, hopefully, a gradual movement today toward authentic scientific methods – decent evidence, proper typologies, better hypotheses, practical and ethical tests, in collaboration with the very public we are trying to help. Combining that with the experiences and input from those in the community who suffer from crime, will help us refine the aspirin that comprises the crime prevention programs of today.

This is the path that will allow us to create livable and safe neighborhoods that our kids can inherit.

.jpg)