|

| Deborah Osborne's new book, Elements in Crime Patterns, delivers a long-overdue typology for crime investigators, researchers, and prevention specialists |

By Gregory Saville

When you think of the study of crime and its prevention, perhaps you imagine that, after a century of criminology, elementary crime patterns are well understood in the academic literature. You would be mistaken! True, we do know plenty about some crime types, as well as the geographical patterns of crime events. But studies about the actual patterns of offenders and offenses are seldom collated together into a coherent, practical dictionary of elementary crime patterns – what scientists call typologies.

For example, in biological science Scottish botanist Patrick Matthews outlined the entire theory of natural selection after years of classifying different types of trees into a typology. Thirty years later that led others, like Charles Darwin, to build more classifications (and claim the theory as his own). Darwin’s bird typologies from the Galapagos Islands, along with Matthews's original work, eventually led to one of the most powerful theories in science – the evolutionary theory of natural selection.

This method of constructing elementary typologies is so well understood by historians that it usually stands as the introductory chapter on virtually every book about the history of science.

Crime science, by comparison, has barely scratched the surface of this type of basic typology. This is an alarming fact since that is how robust theories of explanation and prediction emerge in the first place. It is almost like crime science got ahead of itself and developed theories without the essential first steps of theory building.

Until now!

PRACTITIONER-BUILT TYPOLOGIES

Deborah Osborne is an author, retired U.S. Secret Service intelligence analyst, retired crime analyst with the Buffalo police, and former co-chair of the International Association of Crime Analysts. She is also one of my former students from a short crime mapping and analysis course I ran out of our research center at the University of New Haven 20 years ago. To be clear, by the time she took our training, Osborne was already an established crime analyst with considerable experience.

This week Osborne published her book Elements of Crime Patterns.

I was excited to read her book, especially when I learned that she used a form of AI – ChatGPT – to help her collect data. To my knowledge, Osborne’s book is the first published criminological work to tap into the power of AI as a tool to build a robust database for a criminological text. That itself is an achievement.

|

| Scientific theories emerge from detailed observations and typologies |

CONTEXT IS CRUCIAL

Elements of Crime Patterns is a field guide to identifying crime patterns, a practical toolkit that offers “the kind of knowledge about the crime pattern domain that is learned only on the job through experience” (p. 310). In other words, this is (finally!) the kind of fundamental scientific research that normally precedes theories and prevention programs.

Osborne’s approach is not to provide explanations or theories accounting for where and why something happens. She takes another tack:

“The solution to crime pattern detection cannot be solely data driven. The informal exchanges of information through conversations, explorations, and intuitive perceptions are crucial in investigative casework, but researchers and policymakers often do not acknowledge this. It is important to understand that conversations between law enforcement staff are [the means by which] some crime patterns get recognized, especially those involving separate records system in other jurisdictions…Context is crucial.” (page 21)

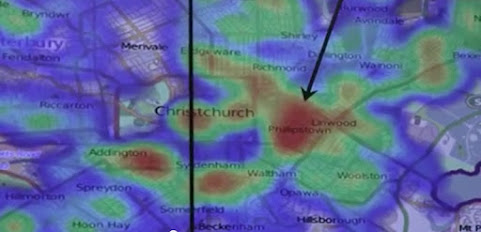

|

| Crime patterns in criminology are often associated with geographic maps of crime hotspots - there are many other equally useful patterns |

TYPOLOGIES OF CRIME

I did have a few issues with the book. It could use an index and a bibliography (although to be fair, each chapter had endnotes with some references). I was also not as keen on a few earlier chapters on lifestyle, tools and equipment, and routine activities compared to later chapters. Those earlier topics seemed to me too generic and all-encompassing to be of much value in analysis. The routine activity theory has been criticized as, at best, an untestable theory and at worst, wrong.

Those points pale in comparison to the impressive 30 chapters on specific crime types. She includes robbery, counterfeiting, sexual assault, murder, drugs, human trafficking, hate crimes, and vehicle crimes, among others. There are also surprises with crimes that make only rare appearances in the criminological literature – wildlife and forest crimes, cultural property crimes, and intellectual property crimes.

The patterns she identifies include methods of different crimes, offender planning and target selection, the aftermath of crimes, and factors that influence crime opportunities. CPTED practitioners should take note there is an especially succinct summary of the opportunity factors that contribute to crime conditions. I wish I had access to information like this long ago in my crime prevention and investigation career. It would have made the work so much easier.

This book is a breakthrough for the science of crime and prevention and for the criminological enterprise – both academic and practitioner. Osborne has made a contribution of considerable weight. This is a book you should read.

_02_(cropped).jpeg)